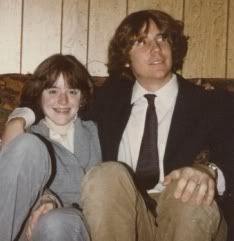

I stole this picture of my mom. And many more like it...I confess. Of course, "stole" is in the past tense, because once Maryann had passed away, I inherited all of her memorabilia. But this one I extracted from her New York apartment before she died, spiriting it back to my home base in the Maine woods so that I could scan it very large, and absorb it. Mom wasn't fond of my obsession with the leavings of her life--I memorized her high-school yearbook as a little girl, I pored over letters and Christmas cards she'd saved, and I burned the chronology of how she looked year-to-year into my mind. I know she thought I was odd for wanting to know so much, and for craving nostalgia from her that did not exist. One of the greatest arguments we ever had, actually, was sparked by my interest in family pictures. She raged at me that I must be crazy wanting to have all those faces up on my walls at home. (Don't worry, her counterpoint never swayed me for a second. It wasn't the first time that our opinions had been so diametrically opposed--no, I had invested decades in doing the opposite of whatever she would.)

This photo lived in her professional scrapbook: an imposing, black-covered, slippery-paged tome that was filled with press clips, telegrams from Broadway openings, 8x10 glossies, and other showbiz detritus. Undeniably, my mother was the least glitzy performer ever. Just look at her up there: she dressed beautifully, I'm not saying that, but look at her posture and her expression...and her nimble, blurred-in-motion hands. It's all about the music. Maryann did not get into playing piano for fame, fortune, or even attention. I'm not sure she even got into it because she wanted to. I believe she began to play piano because she was compelled by a powerful, overwhelming blend of innate talent and deep-seated alienation from the people around her. That doesn't differentiate her from other musicians, I'll grant you--but it sure as hell sets her apart from most people's mothers.

What did she hear in the music that she created? And what of the music that others performed, which she owned in recorded form and treasured? I wish I could ask her, but even if I did, she'd shrug off the question or give me a filmy half-answer. Mom was not a music librarian or completist (that was my rubric), but when she loved a performance, you can bet you'd be hearing it over and over in her household. Fats Waller. Count Basie. Oscar Peterson. Jimmy Smith. Ella Fitzgerald. Peggy Lee. Her chronology, her nostalgia was aural, rarely visual or verbal.

Another thing that set my mom apart from other mothers was her propensity for keeping me awake late. Jazz musicians are nighthawks; thus, much of the musical education she imparted to me was shared long after my peers were tucked in with a teddy. We went to Broadway shows, my dressy patent-leather shoes sliding on red carpets and giving me blisters as we searched for our seats. Sometimes we went to clubs or smoky restaurants to hear one of Mom's old friends play.

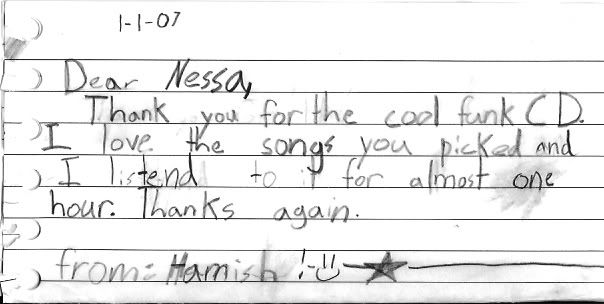

Even at home, she would wake me from a sound sleep and implore me to come into the living room to hear something. "You have to hear this, Nessa," she would say. "Listen. Do you hear it?" While her career had largely been forged in jazz, the music she woke me up for was invariably classical. I can still revive my feelings of grumpiness as I shuffled into the dimmed living room, wincing at whatever lamplight there was. "Do I have to?" I would whine, but she ignored me. Respighi, Stravinsky, Ravel...swirls of intoxicating, cascading, now-dissonant, now-resolved orchestral pieces. Romantic--I should say so, to the extreme. Completely contrary to my mother's everyday demeanor of distant practicality. As I snuggled alongside her on the sofa, leaning in a desperately sleeplike posture, she would regale me with stories of the composer's visions whilst writing the piece. She would also describe the revilement of contemporary audiences when some of these pieces debuted. How these composers were misunderstood, untouchable, way ahead of their time.

I remember Daphnis et Chloe most vividly. I never could catch the gist of the romance Ravel was depicting in this piece, no matter how many times Mom explained it. Instead, while I sat there, I was tugged by two distinct emotions: admiration for my mother's full-hearted bliss as she experienced this lush recorded music, and embarrassment that she was so ridiculously fond of it. The music seemed somehow maudlin and unseemly to my kiddie mind. I wanted to feel the swoops in the pit of my stomach as the crescendoes rose and burst, but this extravagant expression of prewar beauty was beyond my ken.

I wonder now if my parents had listened to these classical pieces early in their own romance, before things turned sour and negative. Tucked onto her single-mother sofa, was she revisiting snowy Montreal, the cosmopolitan isolation booth of a city that hosted their few happy years as young marrieds? Was that why her classical listening sessions were dampened by tears, always?

I can't play an instrument. In fact, I resisted Mom's attempts to teach me piano rudiments because I felt above those single-note lessons. She, in turn, steadfastly refused to flip past the first pages in the book, to see if I was somehow more gifted than the average student. I needed a solid foundation before I could start really playing, she insisted. I needed to know which keys were matched to which fingers.

Wasn't gonna happen. I'm too much of a free-associating creative type to follow the marching ants of sheet music. But I did inherit one shining thing: all of my memories are swathed in music. I find artists who speak to my sensibilities, and I return to them again and again. The past is brought vividly back as I listen, and every chance I get, I will see those performers in a live venue.

Yeah, sometimes I cry, too. I apologize to my embarrassed 6-year-old self whenever that happens, but I tell myself: I'm powerless. I can't help it. Give in.

"Just as appetite comes by eating, so work brings inspiration, if inspiration is not discernible at the beginning." --Igor Stravinsky

What did she hear in the music that she created? And what of the music that others performed, which she owned in recorded form and treasured? I wish I could ask her, but even if I did, she'd shrug off the question or give me a filmy half-answer. Mom was not a music librarian or completist (that was my rubric), but when she loved a performance, you can bet you'd be hearing it over and over in her household. Fats Waller. Count Basie. Oscar Peterson. Jimmy Smith. Ella Fitzgerald. Peggy Lee. Her chronology, her nostalgia was aural, rarely visual or verbal.

Another thing that set my mom apart from other mothers was her propensity for keeping me awake late. Jazz musicians are nighthawks; thus, much of the musical education she imparted to me was shared long after my peers were tucked in with a teddy. We went to Broadway shows, my dressy patent-leather shoes sliding on red carpets and giving me blisters as we searched for our seats. Sometimes we went to clubs or smoky restaurants to hear one of Mom's old friends play.

Even at home, she would wake me from a sound sleep and implore me to come into the living room to hear something. "You have to hear this, Nessa," she would say. "Listen. Do you hear it?" While her career had largely been forged in jazz, the music she woke me up for was invariably classical. I can still revive my feelings of grumpiness as I shuffled into the dimmed living room, wincing at whatever lamplight there was. "Do I have to?" I would whine, but she ignored me. Respighi, Stravinsky, Ravel...swirls of intoxicating, cascading, now-dissonant, now-resolved orchestral pieces. Romantic--I should say so, to the extreme. Completely contrary to my mother's everyday demeanor of distant practicality. As I snuggled alongside her on the sofa, leaning in a desperately sleeplike posture, she would regale me with stories of the composer's visions whilst writing the piece. She would also describe the revilement of contemporary audiences when some of these pieces debuted. How these composers were misunderstood, untouchable, way ahead of their time.

I remember Daphnis et Chloe most vividly. I never could catch the gist of the romance Ravel was depicting in this piece, no matter how many times Mom explained it. Instead, while I sat there, I was tugged by two distinct emotions: admiration for my mother's full-hearted bliss as she experienced this lush recorded music, and embarrassment that she was so ridiculously fond of it. The music seemed somehow maudlin and unseemly to my kiddie mind. I wanted to feel the swoops in the pit of my stomach as the crescendoes rose and burst, but this extravagant expression of prewar beauty was beyond my ken.

I wonder now if my parents had listened to these classical pieces early in their own romance, before things turned sour and negative. Tucked onto her single-mother sofa, was she revisiting snowy Montreal, the cosmopolitan isolation booth of a city that hosted their few happy years as young marrieds? Was that why her classical listening sessions were dampened by tears, always?

I can't play an instrument. In fact, I resisted Mom's attempts to teach me piano rudiments because I felt above those single-note lessons. She, in turn, steadfastly refused to flip past the first pages in the book, to see if I was somehow more gifted than the average student. I needed a solid foundation before I could start really playing, she insisted. I needed to know which keys were matched to which fingers.

Wasn't gonna happen. I'm too much of a free-associating creative type to follow the marching ants of sheet music. But I did inherit one shining thing: all of my memories are swathed in music. I find artists who speak to my sensibilities, and I return to them again and again. The past is brought vividly back as I listen, and every chance I get, I will see those performers in a live venue.

Yeah, sometimes I cry, too. I apologize to my embarrassed 6-year-old self whenever that happens, but I tell myself: I'm powerless. I can't help it. Give in.

"Just as appetite comes by eating, so work brings inspiration, if inspiration is not discernible at the beginning." --Igor Stravinsky